A SHORT STORY

OF THE MAKING

All of We speaks for itself. To me, making All of We, has been a voyage of immense challenge and great learning on both an anthropological, ethical and personal level. I find it important to offer a little context and thus share this short story of how and why All of We was made.

THE CENTENNIAL 2017

The 31st of March 2017 a rather ambivalent celebration took place in both the United States Virgin Islands (USVI) and Denmark. This day marked the 100 year anniversary for Denmark selling the former Danish West Indies; St. Thomas, St. John and St. Croix, to the USA for 25.000.000 dollars in 1917. This was done on the basis of a referendum in Denmark, while the inhabitants of the three islands were never included in the decision.

I was studying Visual Anthropology at Aarhus University at the time, and was struggling to decide where to do prolonged fieldwork for my master thesis. During the spring of 2017 Danish media were suddenly writing about Danish colonial history in the Caribbean. I was highly indignant by the fact that at no time during 16 years of lower and higher education had I been introduced to this significant part of my country’s history. I suddenly remembered glimpses of a horribly racist TV-show taking place by a yellow fort on St. Croix and even meeting a senator from St. Croix in Denmark, as a child. I was drawn to use time among people on St. Croix, feeling like a lost connection had peaked out of this vast neglect in Danish national memory.

All Of We is made from material done during a fieldwork for a Masters in Visual anthropology at Aarhus University, Denmark.

The fieldwork was done on St. Croix during 4,5 months through August-November 2017 and January-February 2018 by the Danish student Freja Sindberg.

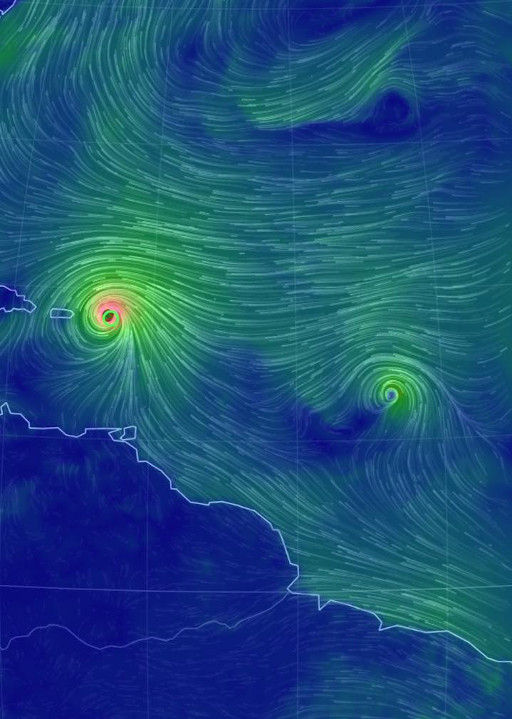

The 6th of September 2017 hurricane Irma hit the Caribbean followed by Hurricane Maria the 19th of September. In the USVI 90% of the buildings were damaged by the storms and about 13,000 constructions were roofless. For months to come, residents of St. Croix were struggling with a devastated infrastructure, lack of power, and scarce subsistence resources.

ARRIVING ON THE ISLAND

Even though postcolonial indignation sparked my motivation to do fieldwork on St. Croix, I did not want to force colonial history or Denmark as main focal points. Rather it was important to me to arrive open and curious to the reality and concerns of inhabitants at the present moment. Before arriving on St. Croix I had been blessed to meet Solange at a West Indian folk party in Denmark. On her generous invitation I was able to stay with her and her mother in the middle of the island for the first period of my stay. Born and raised on St. Croix, Solange was able to introduce me to many people in the local community on the West side of the island, while I reached out to others myself. Many tracks quickly seemed to point west, so I soon moved to Frederiksted where I could stay with Benny, a childhood friend of Solange. In this early stage of the fieldwork, I was perplexed to hear many people express concerns about the crucian1 culture dying out. I asked myself; how can a culture die? And why is this so important? Drawn to the theme of cultural heritage, I started to meet with several Culture Bearers2 of the Island, and to cooperate with CHANT, documenting a cultural restoration and education program called the Free Gut Project3.

NOTES

1 Crucian is a local expression for culture tied specifically to St. Croix.

2 Culture Bearers is a local term for people who are acknowledged for their effort to keep local culture alive, such as the art of Moko Jumbies or Calypso music - a tradition of political and often satirical music historically used to transfer news from plantage to plantage without the slave owners noticing.

3 Crucian Heritage and Nature Tourism (CHANT) launched the Free Gut project as part of a larger program called Invisible Heritage: Identity, Memory & Our Town. See more at //chantstx.org/invisible-heritage/

THE HURRICANES

Everything changed when the first warning of a category 5 hurricane reached St. Croix, barely three weeks after my arrival. I watched uneasily while Benny closed down the beach house with shutters and other severe preparations. We then went to the concrete house of his father to wait out the storm. Hurricane Irma left St. Croix mostly with the scare while St. Thomas and St. John were severely hit. The public atmosphere was now marked by relief and solidarity with the islands dealing with vast destructions, until rumors of another hurricane reached the shores. On September 19th hurricane Maria swirled directly into St. Croix. Back in Benny’s family house, I realized that this was an extraordinary storm, even for the islanders around me, that seemed so cool and prepared for these mighty forces of nature. I have never heard wind screaming like this, high pitched and resembling human voices carving into the marv of bones, the sense of air pressure threatening to blow off the roof. At this moment I knew this hurricane would inevitably shape life on the island for a long time and I decided to use the camera as a way to explore what was happening around me. The film ‘All of We’ thus came to life as an ethnographic exploration of this extraordinary moment in US Virgin Island history, using filmmaking as a way to intuitively analyze and engage with this new and unforeseen reality of a natural catastrophe.

WATCH ALL OF WE

SYNOPSIS

In All of We, we follow the anthropologist and filmmaker’s way into the local community on St. Croix, when two catastrophic hurricanes hit the Caribbean Island. Caught in the middle of the storm, we come close to a local family dealing with the horrors of the night and the chaos the daylight exposes. With all infrastructure wrecked, house roofs gone and the perspective of months to come without electricity and water, we meet islanders showing an extraordinary calmness and gratitude to life. Yet, the aftermath also spurs up ambivalent reflections on the state of the local community. Four islanders; a calypso king, a young radio host, a painter and a spiritual elder, use the camera as a direct channel to speak to st. Croix. These expressions are weaved into atmospheric scenes of public life in the hurricane aftermath forming a mosaic that reflects local and universal questions of migration, postcolonial shame, spirituality and the longing to belong.